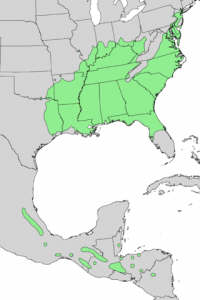

If you are fortunate enough to escape the winter cold and travel to warmer destinations in Central America, keep an eye out for one of our eastern native trees: the sweetgum has an extensive range, growing in the mid-elevations of cloud forests in Mexico, down into Nicaragua.

If you are fortunate enough to escape the winter cold and travel to warmer destinations in Central America, keep an eye out for one of our eastern native trees: the sweetgum has an extensive range, growing in the mid-elevations of cloud forests in Mexico, down into Nicaragua.

With five (occasionally seven) lobes, they resemble maple leaves but are less palmate and more deeply defined. In comparison to maples which grow in pairs, the sweetgum leaves are alternate.

In Virginia, they live more commonly in the piedmont and coastal plain but occasionally, they can be found growing naturally in the Shenandoah Valley. They make spectacular specimen trees as they have numerous interesting aspects – from bark to autumn color to charming star-shaped leaves.

In summer, sweetgum provide wonderful shade with heights up to 150 feet and maximum crown spread of 100 feet. When mature, they have a pleasing, balanced, rounded form.

The young twigs and limbs have distinctive flanges and wing-like growths. Due to this “extra” wood on the branches, they are prone to ice damage as snow and ice can build up in the crevices, weighing down the twigs and limbs. This growth has earned the sweetgum the nickname of “alligator tree” as the young branches have a scaly, vaguely prehistoric appearance.

Sweetgums prefer full sun and rich, well-drained soil. It requires planning when used as a landscape tree due to its mature size and this tendency for ice damage, particularly when young. It develops a significant root system, necessary for anchoring such a tall tree, making it best suited far away from sidewalks and buildings.

The woody, spiky seed balls also make the tree best suited to areas where they can grow unimpeded and where they can drop their seeds where vehicles and bare feet will not mind them.

It is always informative to delve into the Latin names of plants: Liquidambar styraciflua comes from liquidus meaning “fluid” and Arabic “amber”; styrax is Greek for the storax tree. So this tree is named for the resin which flows when the bark is wounded. It also gives the twigs a pleasant taste when chewed and emits an aromatic odor.

In his wonderful compendium of stories collected from old-timers, mountain folk and Cherokee elders in the Appalachians, John Parris interviewed his grandfather who spoke of “gummin’ time” in the spring when sap was flowing. “When I was a boy…there wasn’t no store-bought chewin’ gum to be had. We got our chewin’ gum out of the woods’. He reported that they most often got their gum from pine resin but that spruce and birch were also prized. ‘Sweet gum made another mighty fine chewin’ gum. But it was somewhat bitter tasting.’ He notes that it is also ‘mighty good for treatin’ sores and skin troubles’[1].

‘When sweet gum bark is wounded, it exudes a vanilla-scented resin known as storax or styrax, which is used in perfumery and also as a medicine (as an expectorant and inhalant and to treat skin diseases’[2]

Southampton, Virginia claims the Commonwealth’s award for the largest known specimen with a height of 145 feet, circumference of 236 and a crown spread of 92 feet. The national champion grows in Burlington, NJ and tops out at 115 feet, has a circumference of 230 feet and a crown spread of 109 feet.

In addition to these champions, Virginia has a record of remarkable trees, chosen for their large size, age, significant history, beauty or beloved community status. In 2008, Remarkable Trees of Virginia was published, filled with beautiful photographs highlighting these honored trees. A significant sweetgum flourishes in Johnson Park, South Norfolk. Estimated at about 200 years old, this tree is protected by residents who realize its significance in their community, an appreciative city arborist and an engaged Parks and Recreation Department[3].

As if the sweetgum tree needed any other reasons to recommend it as a wonderful addition to the landscape, it is the host of one of the most intriguing and exotic of the night-flying moths: the luna moth. It also provides food for baby Promethea moth, another spectacular Virginia native caterpillar.

As if the sweetgum tree needed any other reasons to recommend it as a wonderful addition to the landscape, it is the host of one of the most intriguing and exotic of the night-flying moths: the luna moth. It also provides food for baby Promethea moth, another spectacular Virginia native caterpillar.

Finally, the virtues of sweetgum continue into the commercial realm; its timber is only second to oaks among hardwood production and its wood, which can take a high polish, is used for ornamental woodworking in cabinetry, veneer, baskets, boxes, etc.

Chris Anderson

Executive Director

White House Farm Foundation

[1] Parris, John, 1957, My Mountains, My People, Citizen Times Publishing Company, Asheville, NC., p.219.

[2] Tudge, Colin, 2005, The Tree – A Natural History of What Trees Are, How They Live, and Why They Matter, Crown Publishers, New York, p. 168.

[3] Hugo-Ross, N & J. Kirwan, 2008, Remarkable Trees of Virginia, Albemarle Books, University of Virginia Press, p.77